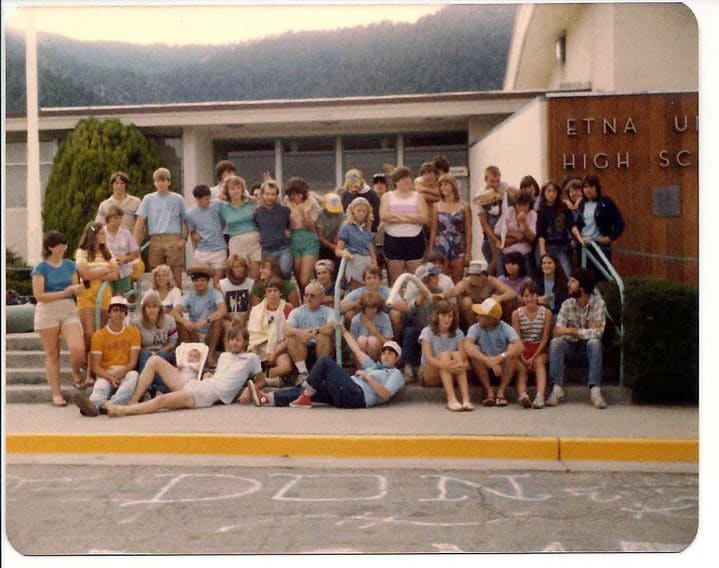

Editor’s Note: Today marks 40 days until the 1st work day of SSP’s 40th summer of service. Each day we will highlight one year of SSP’s history until June 29 which will kick-off the 2015 summer. Today reflects on 1975.

By Rev. Dave Wolf

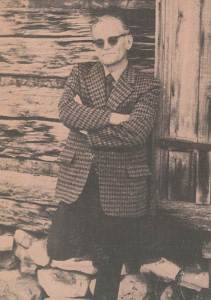

The Rev. Tex Evans, then with a national board of the United Methodist Church, had once served a small denominational church in Big Pine, California. On a return visit, after many years had passed, he was appalled by the living conditions of the Native Americans, whose people had lived there long before the arrival of the whites. Tex, who was deeply involved with the Appalachia Service Project (ASP), worked to recruit volunteers to repair and rehabilitate houses in that area. Tex challenged Floyd McKeithen to gather some volunteers to lend a loving hand to the indigenous natives of his old parish.

Floyd, son of United Methodist California-Pacific Conference minister David McKeithen, was a recent college graduate. Floyd had worked with Tex and, like most people, could not say “no” to him.

I do not recall how we made the connection, but I joined up with Floyd either in Big Pine or in Sacramento, where I served St. Mark’s United Methodist Church. We planned for that first project, which included youth from St. Mark’s and at least one other church from Floyd’s conference. Tex followed through with his promise to provide some funds and a couple of staffers from ASP to show us the way.

The next year, we were on our own, except for some ASP funding. We followed up the second year at Big Pine, and eventually moved the site to Bishop, as the local Presbyterian church could accommodate a larger group.

From the beginning, Floyd was the spark plug organizer and key leader. We formed a committee with representation from both conferences. Floyd was the executive director and I was the committee chair for several years, doing paperwork at the capitol for the incorporation of the organization, which was related to our two United Methodist Conferences.

From the beginning, Floyd was the spark plug organizer and key leader.

I took the concept and proposal for a youth volunteer program to work with Native Americans within the bounds of our respective conferences to our administrative council. The response was cool, but finally we were accepted and related to the Board of Missions.

Floyd went through the process in Southern California, with the support of his father who was influential in the conference, and served on the board before and after incorporation. The reason we incorporated was, in part, to have more opportunities for outside funding and to have more status as we approached local tribal councils, as well as other tribal organizations.

Early on, we worked with the California Tribal Council until it dissolved. Fortuitously, its office was only a few blocks from St. Mark’s, which allowed me to get to know the staff. Floyd worked directly with the CTC’s executive director who suggested work sites. He gave Floyd a referral as he negotiated with the tribes to set up arrangements for the teams to come. Strong and loyal staffs were cultivated as SSP grew in numbers and successes. The rest is history.

Strong and loyal staffs were cultivated as SSP grew in numbers and successes. The rest is history.

In those early years, we soon established the approach wherein we would have two projects. One would be in the California-Pacific Conference and the other in the California-Nevada Conference. In possibly the fifth or sixth year of our existence, we dared to move to three and more sites, even then having the long-range view of bringing other UM Conferences on board.

One story was told and retold about the old Indian, let’s call him Old Joseph, who lived in the country outside of Big Pine near the intersection of a road, which took off to the west from highway 395. He had been embroiled in a confrontation with a neighbor regarding the water supply for his run-down cabin. He was an angry, lonely man who had no source of pride or friendship. One of our teams refurbished his home inside and out, giving it a fresh coat of paint, as well as working on the waterline to the agreement of both Joseph and the neighbor. The water came, his garden grew; he shared his food and found friends. The next year when some of the team visited him, he would pause to wave at the passers-by. He said with a smile and sense of dignity, “People just used to go by…now they honk!” More than a house went through a transformation.

“People just used to go by…now they honk!”

Not only did we help people sorely needing a hand, we learned a great deal. This was the late 1970’s, and through their own growing sense of identity, the work of tribal organizations, and the encouragement we were able to offer, we saw a sense of pride evolve.

Young members of the Hoopa reservation lectured our youth on the sacredness of the river and how not to discard trash along the banks (which we would not have done anyhow), as some whites tended to do. At Sawyer’s Bar we were asked to help remove vines and other growth which had basically buried a ceremonial house. We considered it a privilege to help revive not only the house, but to help revive their culture by helping them put the house to use again. We saw respect for the elders, but at the same time, wondered why the elders were not provided with more “hands-on” assistance by their families. On occasion we invited a young family member to join us on the roof to help lay out the new roofing material. We followed the maxim of Tex Evans, “We help people as they are, where there are, with no strings attached.”

We followed the maxim of Tex Evans, “We help people as they are, where there are, with no strings attached.”

One highlight for the youth and counselors from St. Mark’s was when we received a request from a tribal organization to host a group coming to an inter-tribal affair in Sacramento. They knew they could depend on us and be safe. Some of the Native American youth had not been on the west side of the Sierra mountains. We had dinner for them in the basement social hall and housed them in the homes of the congregation. We felt honored.

We saw a different culture at Sawyer’s Bar. We were working in the home of a Yurok and former millwright who retired because of severe health issues. We were installing sheet rock in the upstairs bedrooms, running back and forth between the garage and where we were working. He had a fine bunch of tools from his working days. His house was on the main street of town that was also the road that ran from Etna over the mountain and through the deep valleys cut by the Salmon River. To our amazement, in spite of those valuable tools, there were no doors on the garage that opened on that main road! When we inquired, the Native gentleman said simply, “People don’t steal around here.” One of our vehicles, a station wagon, broke down and was left on the road “up river” for three days. There was a new tire visible in the backseat. When we went to retrieve the car, we found nothing had been touched. Our Yurok friend seemed to be right.

The early Northern California sites included Etna, Somes Bar, Sawyer’s Bar, Hoopa, Fresno, Burney, Ione, and Happy Camp. Southern sites were often around Julian, Bishop, and Big Pine.

From that seed, a strong, sturdy and prolific plant has grown. I am also sure that the statement made about United Methodist Volunteers in Missions also applies to SSP. For the participants it is still “a spiritual experience disguised as work.”

“[…] a spiritual experience disguised as work.”