By Francesca Gazzolo, SSP Staff Alum 2018-2020

A little over two years ago, I was standing in the windy, sparsely-shrubbed desert just outside Bethlehem. A fence about twenty feet high stood a few yards away, interwoven with barbed wire. I had just visted one friend in Tel Aviv and was now spending the day with another who did legal aid work for Palestinian refugees. The difference between this desert village and the palm-tree-lined, commercialized city on the Mediterranean was drastic.

I was in “Area C,” the part of the occupied West Bank under the jurisdiction of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). One of the aid workers led us towards the home of a man named Omar. We walked through an IDF-controlled gate to Omar’s stone house – one of the few residences still standing in the area.

Since leaving the property alone for even a few hours could open it to occupation by the Israeli government’s settlement program, Omar or his wife had to be physically present at all times. I sat in his home, drinking Arabic coffee, and met his children – who have never left their house with both of their parents.

Before I visited the Holy Land, I usually kept quiet in conversations about the conflict between Israel and Palestine. I grew up in a suburb of Chicago with a large Jewish population, and many of my friends had family in Israel. Others claimed little connection to it or actively opposed the Israeli government. We didn’t learn about the conflict in school, so I just stayed in my lane. I had decided it wasn’t “for me” to speak on.

You might be wondering why I’m writing about it now. There comes a time when those who are uninvolved can no longer oscillate between “both sides.” As the followers of Jesus, a man who “came to set at liberty those who are oppressed,” we must always ask ourselves, “what is my role in the struggle?” Our roles may change. Sometimes, if we are not part of a struggle, our role is to listen. I think this moment is different.

As the followers of Jesus, a man who “came to set at liberty those who are oppressed,” we must always ask ourselves, “what is my role in the struggle?”

For years, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been “off-limits” in the political sphere, even among progressives. But the recent violence on the Gaza Strip has made it all but impossible to maintain that pseudo-neutrality. For the first time in America, we are seeing a tide of voices swell in public support of the Palestinian people.

In order to understand what is going on today, we must understand how this conflict – or more accurately, this struggle – came to be. Its history has been so twisted and weaponized over time that it is now one of the best examples of history as many stories – messy, ambiguous, and often contradictory stories. Right-wing supporters of Israel (many of them evangelical Christians, ironically enough) would have us believe that Israel was founded from a collective effort of the worldwide Jewish diaspora, a move towards self-determination by an oppressed community, independent of any meddling by colonial powers. They would have us believe that the Palestinian people aren’t Indigenous, nor are they a “people” at all – just an amalgam of various Arab tribes, committed to Israel’s destruction.

The Palestinians resisting occupation tell very different stories. Palestinians are native to the Holy Land, and before the project of Israel took hold, Palestinian Christians, Muslims, and Jews coexisted relatively peacefully. Thanks in large part to imperial Britain’s interference, the state of Israel was born in 1948. The day Israel was founded, the nakba (“catastrophe” in Arabic) claimed hundreds of Palestinian villages, forcing more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes. Many of those who did not leave were killed or pushed into refugee camps.

Israel is not, and never has been, the collective effort of all Jewish people towards self-determination. Zionism began as the quest for a Jewish homeland, but even from its beginnings, there was opposition in the Jewish community. This opposition waxed when Britain became involved in an ill-fated attempt to carve up the recently-fallen Ottoman Empire, then waned again after the horrors of World War II.

After nearly a century of fighting between the Israeli state and a nation of Palestinians with little political cohesion, Israel now claims the majority of the territory between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. It has one of the most advanced military-industrial systems in the world, including a state-of-the-art missile defense system known as the “Iron Dome.” It subsidizes a settlement program that forcibly evicts Palestinians from their homes and pays Israeli citizens to occupy them.

Many view this as an attempt to create “Swiss-cheese” holes in Palestinian communities, making a two-state solution geographically untenable. Palestinians who do remain in their homes are subjected to Israeli surveillance round the clock. Palestinians – and even Jews of color – in the state of Israel face housing discrimination, poor job prospects, and racial profiling by the Israeli police.

For right-wing Israeli leaders, the goal is a single, ethnonationalist state. The goal is to suppress every Palestinian uprising against colonialism until the spark dies out.

I take great care to separate the Israeli state as a settler-colonialist project from the lives and choices of the Jewish people who reside in Israel – and from the 15 million Jews in the world, the majority of whom live outside Israel’s borders. When I write about ethnic cleansing and apartheid, I am not writing about the Jewish families who fled to the Holy Land during the Holocaust because no other country would take them in. It is difficult to compare this struggle to other colonial projects because of the political and religious repression, forced removal, and genocide the Jewish people have endured throughout history, both ancient and recent.

So how, you may ask, can we use those same terms for Palestinian history? Isn’t that a contradiction?

No, because life is life, death is death, people are people, and land is land. Like any other colonized region, the state of Israel was built on land that already had a people. It was, and continues to be, built by taking the lives and freedom of those people.

To be effective allies with any oppressed group, we must always resist over-simplification. Both the Palestinian and Israeli populaces are as multi-faceted as our own. On my trip to the Holy Land, the Palestinian legal aid workers were quick to denounce the violent, anti-Semitic crusades of Hamas and the Islamic Jihad Party. But they were also quick to point out the hypocrisy in Israel’s denunciation of these groups. While Palestinians in Sheikh Jarrah throw stones to protest the violent evictions of Arab families, the Israel Defense Forces fire stun grenades and tear gas during worship services. While Hamas fighters in Gaza launch rockets that kill six Israeli adults and one child, Israel intercepts most of them, sparing their own citizens before retaliating with airstrikes that take 122 Palestinian adults’ and 31 children’s lives.

To be effective allies with any oppressed group, we must always resist over-simplification.

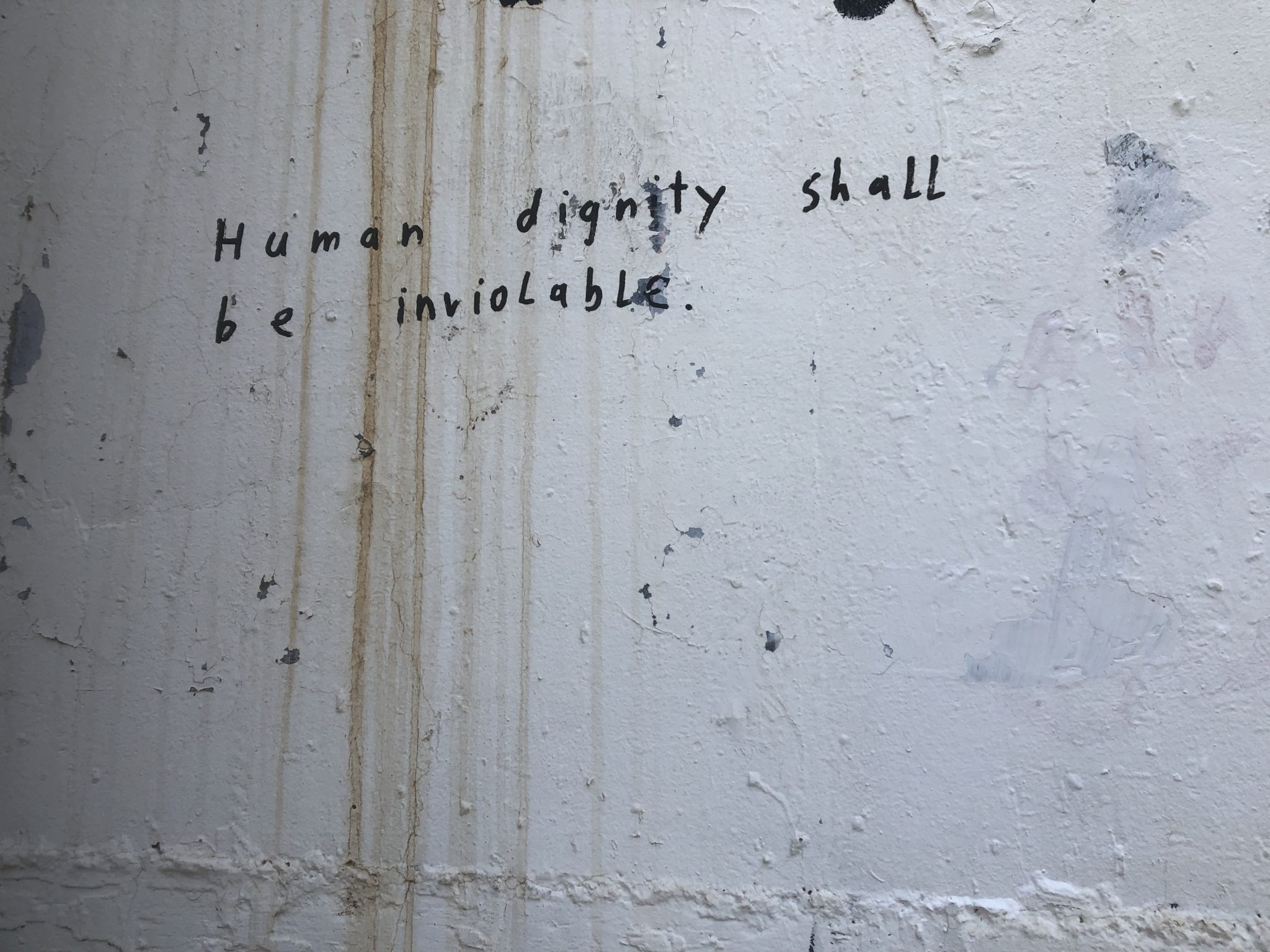

Neither is “justified” in the sense that violence in itself is unjust. As a Christian, I believe to my core that we must never sweep the morality conversation under the rug in favor of cold, utilitarian calculation. Every human life is infinitely valuable. But we must also acknowledge material realities. Israel and Palestine are not equal: Palestinians have no military, no state apparatus, no international supporters who can stand up to the United States, no representation in the Israeli government, no semblance of recourse for the wrongs perpetuated against them; besides their own 6.5 million people living in apartheid. To put it mildly, this is not a fair fight.

I consider myself a pacifist. Violent means have violent ends, and I believe true liberation for any group can only be achieved once all armed violence – interpersonal, state-sanctioned, or paramilitary – is eradicated. But it is easy for me to say that as a white American woman, who has only ever had to confront armed violence as an abstract ethical question. If I were living in perpetual fear that artillery fire could blast my home, my children, or myself to smithereens at any moment, I can imagine my opinion might be more complicated.

Those of us who are removed from the violence often distract ourselves with questions of Israel’s or Palestine’s “right to exist.” People have rights; states do not. The Jewish people who sought safety in the state of Israel have every right to remain in their homes, and the Palestinian people who were exiled – in 1948, in 1967, or yesterday – have a right to return to their native land.

But the Israeli government does not have a right to forcibly and systematically remove Palestinians from their houses under the banner of an explicitly ethnonationalist ideology. It does not have a right to “self-defense” when the “other side” has no defense system to speak of, and when that defense is dependent on disposing of the Palestinian community – root and stem – through eviction, exile, imprisonment, or death. It does not have a right to coerce its citizens into mandatory military service by threatening imprisonment if they refuse to take up arms against Palestinians. It does not have a right to speak for Jewish people the world over.

And no one has a right, no matter how many decades or centuries it has been, to dispossess a person of the land that they and their ancestors have lived on.

On May 20th, Hamas and the Israeli government announced a ceasefire. For all of us who have lent our time or money to this cause in the past few weeks, I worry this will lead to complacency. We all deserve to take a breath and be grateful for the lives that will be spared. But if I have learned anything from activists with far more experience than me, it is that the real work happens out of the spotlight.

Neutrality is no longer an option here. This may be old news for some of you. But for others, I can understand the trepidation you might feel before embroiling yourselves in the most contentious international conflict there is. That’s why the first step is always education.

I am writing to you, the SSP community, because I trust you, I love you, and because I believe allyship with the Palestinian people is part of our broader mission to strengthen and serve marginalized communities.

This organization partners with colonized peoples and helps them realize the future that they determine for themselves. I believe we must do the same for Palestine. Our job now is to learn the histories (plural), listen to the voices of the people who live in the Holy Land, and put our money where our mouths are.

Don’t just take my word for it. Go out there and learn:

- Current news about conflict in Gaza (New York Times, consistently updated)

- A Very Short Introduction to the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict (Very Short Introductions)

- Resources about Palestinian decolonization (Decolonize Palestine)

- Video introduction to the conflict (Jewish Voice for Peace)

- How to have conversations about the conflict (Jewish Voice for Peace)

- Anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism (The Guardian) Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions: FAQs (BDS Movement)

Editor’s Note: “SSP is an affirming and welcoming community that celebrates the lives and love of all people.” We encourage individuals to engage in advocacy alongside marginalized communities. Read more about our mission, inclusion statement, and theology.